Spirituality in Indigenous Japanese and Australian Art

- Scott Barnard

- Sep 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

Parallels in Indigenous Australian and Japanese Spirituality

Although Indigenous Australian and Indigenous Japanese spiritual traditions arise from vastly different geographies and histories, both share a profound reverence for land, ancestors, and the unseen presence of spirits. These parallels are not merely abstract philosophical ideas: they are lived and embodied in practices, rituals, and artworks. By examining the sacredness of land and nature, the presence of ancestors, and the role of art as a vessel for spiritual expression, it becomes clear that these traditions - while distinct - resonate with one another in their vision of a world alive with meaning.

Land and Nature as Sacred

For Indigenous Australians, the Dreaming situates sacred power within the land itself. Mountains, rivers, and deserts are not inert backdrops but active presences shaped by ancestral beings whose actions remain inscribed in Country. These places are not metaphorical; they are direct, living embodiments of cosmology. Similarly, in Japan, Shinto spirituality recognises kami - spirits residing in natural forms such as forests, waterfalls, and stones. Shrines are often built in places of striking natural beauty, affirming that nature is not separate from the sacred but is its dwelling place. Both cultures therefore share a cosmology in which environment and spirituality are inseparable.

Ancestral Presence

The relationship to ancestors also forms a profound parallel. Indigenous Australian stories emphasise that ancestral beings are not confined to the past but continue to animate the present through songlines, ceremony, and Country. Rituals honouring these beings reaffirm human responsibilities to land and community. In Japan, ancestors are venerated through practices such as Obon, a festival where families welcome the spirits of their departed back home. Household altars and memorial rites keep the presence of the dead tangible in everyday life. While the cultural forms differ, both traditions understand ancestors as active participants in the ongoing fabric of existence.

Art as Spiritual Expression

Artworks serve as bridges between the visible and invisible, translating spiritual truths into material form. This can be seen in the work of Japanese contemporary artist Takashi Murakami and Indigenous Australian painter Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Despite their very different cultural contexts, both create large-scale, immersive works that bring spirituality into the realm of colour, form, and lived experience.

Murakami’s painting Japan Supernatural: Vertiginous After Staring at the Empty World Too Intensely, I Found Myself Trapped in the Realm of Lurking Ghosts and Monsters (2019) is a riot of colour and imagery. His work reinterprets traditional Japanese ghost and spirit iconography, filling the canvas with yokai - supernatural beings that blur the boundary between the human and spirit worlds. While dazzling and playful on the surface, Murakami’s painting reflects a deep Shinto-inflected worldview: the idea that the world is inhabited by countless presences, some mischievous, some dangerous, but all real. The sheer scale of the work, and its sensory overload of forms, immerses the viewer in a cosmos alive with spirits.

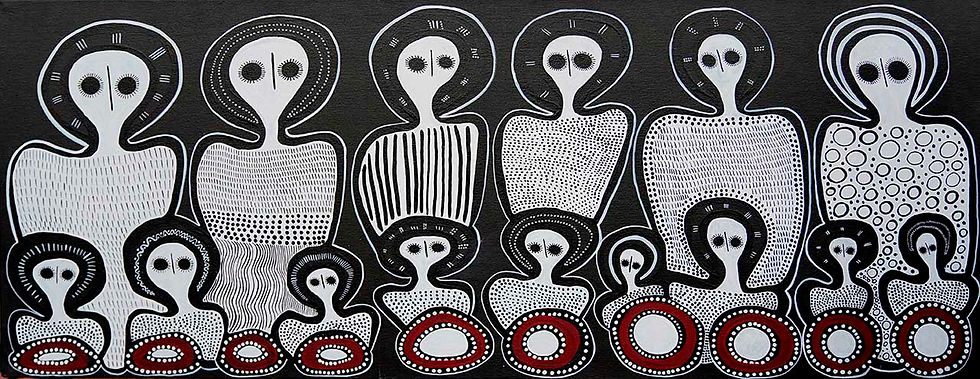

By contrast, Kngwarreye’s Yam awely (1995), painted by an Anmatyerr elder late in her life, appears abstract to many Western audiences. Its sweeping fields of dots and lines in vibrant colour do not depict figures in the conventional sense. Yet the painting is figurative: it represents the yam plant, a vital food source intimately tied to the earth. For Kngwarreye, painting the yam is not only aesthetic but spiritual, since food itself is sacred. To eat is to participate in Country, to be sustained by ancestral gifts. The painting therefore encodes both ecological knowledge and spiritual continuity, showing how nourishment is inseparable from belief.

When compared, these two works demonstrate both difference and resonance. Murakami externalises the spirit world through images of monsters and ghosts, dazzling in their variety, while Kngwarreye internalises the spiritual within the land itself, her dots and lines mapping the life-force of food and Country. Both works, however, collapse the boundary between seen and unseen. They insist that art is not merely decorative but a form of cosmological storytelling. Exhibited in Australia, their juxtaposition also speaks to how cultures far apart can arrive at parallel insights: that art has the power to render spirit palpable and invite viewers into another way of seeing.

Conclusion

Indigenous Australian and Japanese traditions may differ in their rituals, symbols, and artistic forms, but they converge in a shared reverence for land, ancestors, and the unseen presences that animate existence. Their art—whether Murakami’s contemporary vision of spirits or Kngwarreye’s ancestral mapping of food and Country—reveals spirituality not as abstract doctrine but as a living reality embedded in the natural and cultural world. In both, art becomes more than representation: it is participation in the sacred. These parallels remind us that spirituality, across cultures, often begins in the same place—with the recognition that the world is alive.